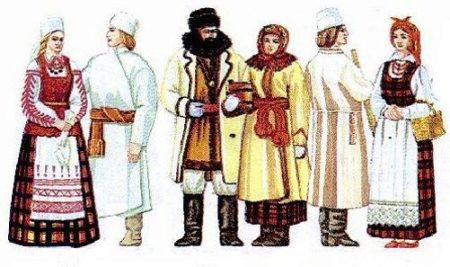

Belarusian national costume

The national costume is a well-established set of clothes, shoes and jewelry. It took shape over several centuries, strongly depended on the climate and reflected the traditions of the people. Natural conditions influenced not only the set of clothes for the costume, but also the choice of fabrics for them. So, for example, the Belarusian national costume, which we will talk about in this article, was sewn from linen, woolen and even hemp fabrics, decorations were made from wood, straw and much more. In a word, from what was at hand.

A bit of history

It is believed that the first information about the outfits of Belarusians is reported by the Statute of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania in 1588. Descriptions and even images of the national clothes of those times can be found in the notes of travelers passing through the lands of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania.

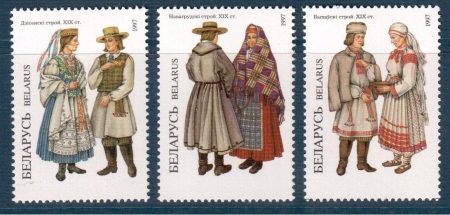

Time passed, the borders of states changed, and with them, folk traditions. By the end of the 19th - beginning of the 20th centuries, the Belarusian national costume already had a single look, in which ethnic features were clearly manifested. Here one could find both ancient pagan elements (mainly in ornaments) and the influence of urban culture. However, the costume was not the same in all parts of the country. Ethnographers count about 22 variants that have developed in different regions: the Dnieper, Ponemanye, Lakeland, Eastern and Western Polissya, etc.Differences were manifested mainly in ornaments, colors and cuts of clothing.

Peculiarities

What is so special about the Belarusian national costume? How does it differ from its closest neighbors - Russian, Ukrainian, Polish costumes?

Colors and shades

The main color of the clothes of the Belarusians was white. There is a legend that it is for this that they got their name. Many famous people noticed this feature during their travels. Thus, the 19th-century ethnographer Pavel Shein wrote about the Belarusian lands in his notes: “...Where people gather, there is a solid white wall.”

Clothes were sewn mainly from bleached linen. This does not mean that Belarusians did not know how to dye fabrics. There is evidence that as far back as the 17th century, peasants dyed fabrics blue, purple and even purple. However, the most favorite color was white.

fabrics

As we said at the beginning, the fabrics were made from local organic material. These were mainly flax, wool, hemp and even nettles. They also brought expensive fabrics, such as silk or velvet, to Belarusian lands. But for ordinary peasants, they were not available.

Until the end of the 19th century, fabrics were made independently in peasant farms. They also painted them themselves. To do this, they used plant roots, berries, bark or buds of trees, and much more. They dyed mainly fabrics for skirts, pants and sleeveless jackets. For other products, the fabrics were simply bleached.

At the end of the 19th century, with the development of factory production, they began to use chintz fabrics, buy bright scarves and scarves. At the same time, elements of urban fashion began to penetrate more and more actively into the national costume.

Cut and decorative seams

The shirt is the main element of the national costume. At first, it was made without seams on the shoulders.The canvas was simply folded in half in the right place and cut in this way. But in the 19th century, this was already considered an outdated method, which was used only for sewing ritual clothes.

A new way to cut a shirt was special inserts (sticks) made of the same fabric that connected the back and front panels.

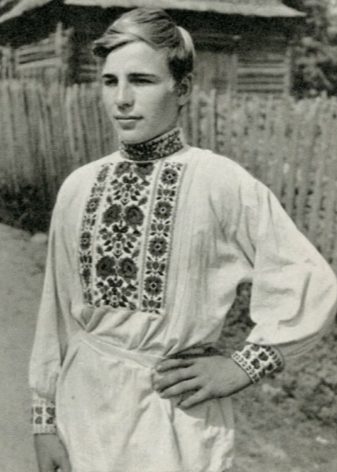

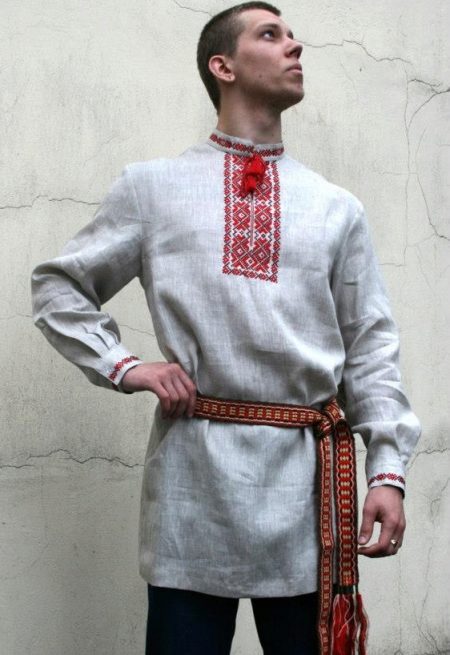

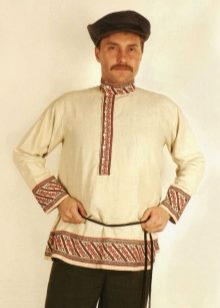

An important feature of the Belarusian shirt was a straight cut on the chest. For example, in the Russian provinces, such an incision was made on the left side of the chest. On festive shirts, special embroidered inserts were added along the slit, which were called “shirt-front” or “brisket”.

Collars were also a characteristic feature of festive clothing. They were made mostly standing, no more than 3 cm, and fastened with a small button. The petty gentry - the poor nobility, who could not confirm their belonging to the upper class and remained in the class of peasants - sewed shirts with a turn-down collar to emphasize their peculiarity. Such a collar was fastened with a cufflink.

Linen skirts were cut from two halves, but when using cloth, they made from three to six longitudinal parts. Then they were sewn together and gathered into folds.

Accessories and decorations

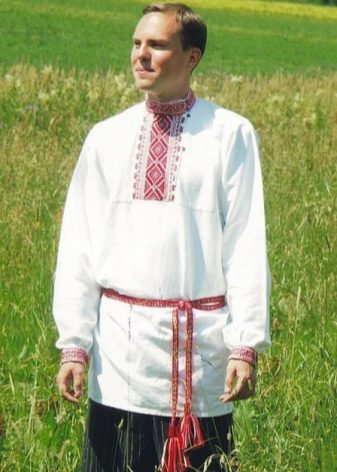

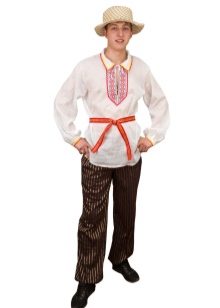

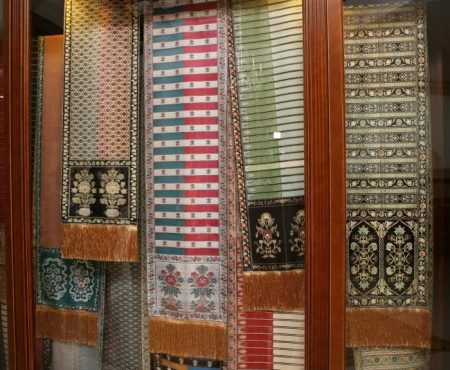

The main accessory of the national costume is the belt. The belts were woven independently, the patterns were the most incredible. The richer the family, the more expensive the belt. According to this element of clothing, the well-being of the family was judged. Very rich people could afford silk belts woven with expensive gold and silver threads. Each such belt is still considered a work of art, to which entire museum expositions are devoted.

Pendants made of inexpensive metals, bone, stone or wood were used as decorations.Women complemented their outfit with beads, mostly glass or amber, wealthy peasant women could wear pearl and ruby. The rest of the decorative ornaments, for example, brooches, rings, bracelets, were available mainly to wealthy peasant wives and daughters and were not widely used.

Varieties

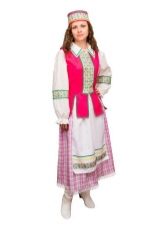

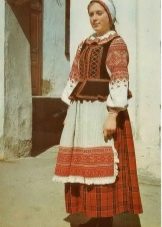

Female

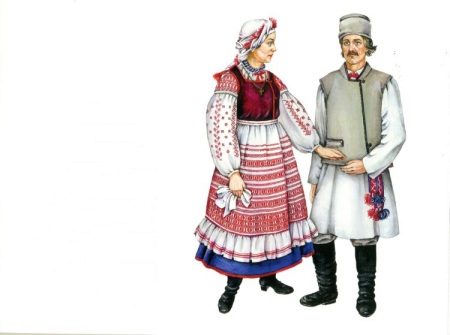

So, the basis of any costume in ancient times was a shirt. Women's shirts were long and made of linen. They were adorned with embroidery. A skirt was worn over the shirt. Skirts could be different: in summer - from flax ("letnik"), in autumn and winter - from cloth ("andarak"), as well as special ones for adult women - poneva. An apron was worn over the skirt, and a sleeveless jacket over the shirt. And girdled. The head was necessarily decorated with a headdress that carried information about the woman's marital status. They complemented the image with beads, ribbons and other decorations. This is the foundation. But there could be options.

The poneva skirt had a different cut and was worn by either married or already engaged girls. Such a skirt was sewn from three pieces of fabric, which were gathered on top of a cord and pulled together at the thallus. If all pieces of fabric were sewn together, it was a "closed" poneva. If they remained open in front and on the side, they called it “swing”. Almost always poneva was decorated with rich ornaments.

The color of the skirt, poneva or andarak could be anything. Mostly painted in red or blue-green. Also, the skirt could be sewn from fabric in a cage or strip. Aprons were always embroidered, and sleeveless jackets were also decorated with lace.

The sleeveless jacket was an element of festive clothing. They made it necessarily on a lining, and called it a “garset”. The cut of the garset could be different: to the waist or longer, straight or fitted. There were no strict guidelines for this.The sleeveless jacket could be fastened with hooks, buttons, or simply laced up.

In winter, outerwear was needed. They made it from wool and animal skins. Most often they wore a sheepskin casing. It was, as a rule, of a straight cut and was decorated with a large turn-down collar. Women's and men's outerwear was cut in the same way. The only difference was that the women's had more jewelry. The sleeves, and sometimes the hem, were sheathed with a strip of the same sheepskin, turned inside out.

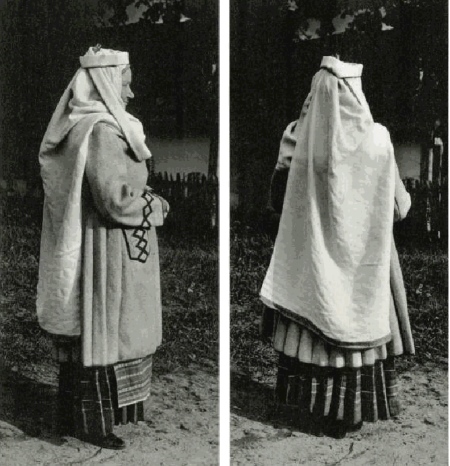

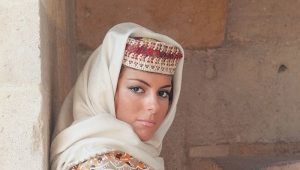

But hats were not as monotonous as outerwear. Girls decorated their hair with ribbons and wreaths. Married women were required to hide their hair. Most often, Belarusians wore a “namitka” or a scarf.

To put on a mitt, you had to collect your hair in a bun at the top of your head and wind it around a frame ring. Then they put on a special cap, and on it - a bleached linen. Its length was on average 4-6 m, and its width was 30-60 cm.

There were a huge number of options for tying namitok. The wedding reminder was kept all their lives and put on again only at the funeral.

Peasant women wore bast shoes or postols from shoes. Postols are special sandals made from raw leather. Boots or shoes were worn only on holidays. Often there was only one couple for the whole family. They made such shoes from shoemakers to order, and therefore it was very expensive.

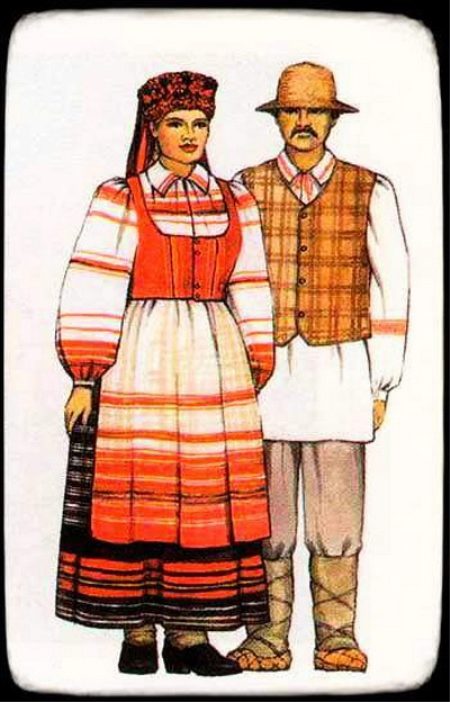

Male

The basis of the men's suit was also a shirt, which was embroidered around the collar and at the bottom. Next, put on pants and a sleeveless jacket. From accessories - a belt and a headdress.

Pants in the Belarusian lands were called "legs" or "trousers". Summer pants were made of linen, winter pants were made of cloth. By the way, because of this, winter leggings were called "cloth".Pants could be cut with a belt and fastened with a button, or they could be without a belt and simply pulled together with a string. Wealthy peasants wore silk over linen legs on holidays. By the way, over time, legs began to be considered men's underwear at all. But this happened at the beginning of the 20th century, when factory-made trousers were already worn with might and main in the village.

At the bottom of the legs, as a rule, they wrapped onuchs and put on bast shoes or postols. Shirts were worn loose.

There were no pockets in both men's and women's clothing. Instead, they used small bags that were worn over the shoulder or hung on the belt.

Men's sleeveless jackets were called "kamiselka". They were made from cloth.

Sheepskin jackets served as outerwear. Wealthy peasants wore fur coats.

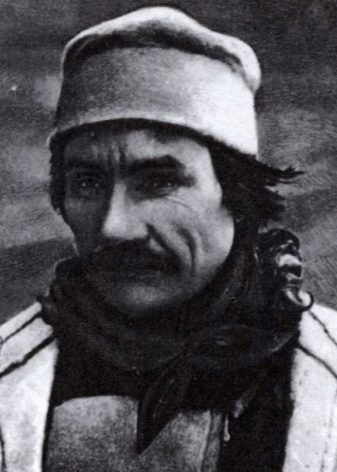

There were a lot of headdresses. They did not carry such social significance as women have and were used for their intended purpose. In the cold season, they wore a “muggerka” made of felted wool, in the summer they put on a “bryl” - a straw hat with brim. In winter, fur hats "ablavuhi" were also used. In the second half of the XIX century. the cap came into fashion - a summer headdress with a varnished visor.

The choice of shoes was about the same as for women. In summer - bast shoes, in autumn and spring - postols, in winter felt boots.

Children's

Children up to 6-7 years old, regardless of gender, girls and boys, wore an ordinary linen shirt to the heels, which was pulled together with a belt at the waist. The first pants were put on for the boy at the age of 7-8, the girls tried on the first skirts at 7-8.

Further, as they matured, new elements were added. So the girl had to sew and embroider her first apron herself. As soon as she did this, she was considered a girl and she could be invited to the company of young people.When a girl was betrothed, she could put on a poneva - a special skirt worn only by adult women. And, of course, the most important element was the headdress. Before marriage, these were wreaths and ribbons, after - a scarf or namitka.

Thanks a lot for the article!